In this blog the early music industry in Australia was analysed in great detail (The Early Record Industry in Australia ? part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5 and part 6). In a four part series on the Australian music business I would like to highlight the recent economic situation of the Australian music industry. In the first part of this series the charts of the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) are analysed to understand the consumers? taste downunder especially in respect to the Australian national repertoire. In the second part the question is answered, which labels benefit from the chart successes of international and domestic artists. In a third part the development of the recorded music sales in Australia from 2000 to 2011 is analysed to give an explanation for the ups and downs in the observed period. In the fourth and last part of the series the economic role of collecting societies in Australia is highlighted especially from the licensing income?s perspective.

In the last part of the series the role of the three Australian music collecting societies ? APRA, AMCOS and PPCA ? for the Australian music industry is highlighted.

?

Three collecting societies licence music on behalf of their members in Australia. The Australasian Performing Rights Association Ltd. (APRA) was established in 1926 by Australian music publishers to collect fees to perform, broadcast and communicate music. In 1979, the Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners? Society Ltd. (AMCOS) was formed to licence music literary or dramtic works for mechanical reproduction, e.g. on physical carriers such as CDs or on digital formats. Last but not least, the Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Ltd. (PPCA) was established in 1969 to represent the interests in the so called neighbouring rights of recording artists and labels.

In total, the three Australian music collecting societies collected licencing fees of AUD?244.1m (EUR?179,7m) in 2011.[1] This is about nearly 2/3 of the recorded music sales in Australia in the same year (see: ?Music Business in Australia ? An analysis of the recorded music sales 2000-2011?). In the following the revenue stream of licencing fees over the years is analysed and the specifities of Australia?s collecting societies?s system is highlighted.

?

APRA and AMCOS are separate not-for-profit organisations. Each has their own Board of Directors elected from and by their membership. Since 1997 the operations of AMCOS has been managed by APRA with the aim of achieving cost savings and efficiencies. Australian and New Zealand citizens and residents, who has been released at least one musical work for sale to the public, can become members of APRA and AMCOS. Since the membership is exclusive it is not allowed to become a permanent member of another collecting society. Music publishers based in Australia and New Zealand can apply for membership in both societies if they have published at least a musical work.

?

The Revenue Streams for APRA/AMCOS, 2000 to 2011

The consolidated revenue (adjusted for inflation) for both collecting societies shows an increase of 58.7 percent to AUD?240.1m from 2000 to 2011 (figure 1).? In 2011, APRA accounted for AUD?183.0m (76.3 percent) and AMCOS for AUD?57.1m (23.7 percent).

?

?

The Australasian Performing Rights Association Ltd. (APRA)

In 2011, APRA earned AUD?159.6m (87.2 percent) from domestic licencees in Australia and New Zealand and AUD?20.2m (11.1 percent) from foreign collecting societies. Further, APRA earned AUD?3.2m (1.7 percent) apart from its core business. APRA?s main domestic revenue source is broadcasting of licenced music by radio and TV stations. In 2011, AUD?91.8m fees were collected, which accounted for more than a half of APRA?s total income. However, in a five years perspective the relevance of broadcasting fees decreased ? despite a modest increase of 2.9 percent in the last five years. In 2007, the broadcasting fees accounted for 56.2 percent of the total revenue compared to 50.2 percent in 2011. The revenue of AUD 37.4m from public performances of recorded music was the second most important income source in 2011. Thus, the performance of recorded music was much more important than the performance of live music in concerts and in public events. Concerts and live music contributed AUD?16.1m to the total income. However, live and recorded music performances have become more relevant in the last five years. Whereas live music and concerts accounted for 6.7 percent and recorded music for 16.7 percent of the total revenue in 2007, the shares increased to 8.8 percent and 20.4 percent respectively in 2011. Although the revenue from digital and online use of music has increased more than three times to AUD?8.7m since 2007, it accounts ?only? for 4.8 percent of APRA?s revenue. In comparison, the use of licenced music in cinemas (not in movies, which is covered by synchronisation rights) cost licencees an amount of AUD?5.6m in 2011, which resulted in a share of 3.1 percent in the total revenue (table 1).

?

?

To sum up, APRA benefited from the increase in the collection of public performance fees, but also by higher payments from broadcasters. Nevertheless the revenue from download and streaming service has grown tremendously in the past five years. Although the growth of digital revenue will decrease in the next few years, there is still potential for further growth.

?

The Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners? Society Ltd. (AMCOS)

The revenue from mechanical fees mainly originates in Australia and New Zealand. In 2011, AMCOS earned AUD?55.1m in mechanical fees, which were paid for ?(?) the manufacture of CDs, music videos and DVDs, the sale of mobile phone ringtones and digital downloads, the use of production music and the making of audiovisual and broadcast material? (AMCOS 2011: 2). Despite the massive decline of revenue from the manufacture of physical products of 47.6 percent since 2007, the overall income from mechanical fees has increased by 3.9 percent and AUD?2.1m (adjusted for inflation) until 2011. The main reason for this increase is the revenue boost from licencing music for download shops. The digital and online fees have been nearly doubled to AUD?21.5m since 2007. Although AMCOS did not report separate figures for dowloading, streaming/webcasting and ringtones for 2011, we can conlude from previous year?s data that the download fees were the main drivers of the increase. In 2010, the revenue from download sales totalled AUD?12.1m compared to AUD?3.0m (adjusted for inflation) in 2007, whereas the revenue from ringtones accounted only for AUD?2.4m and from streaming/webcasting for AUD?0.7. The growth rates for the different types of digital and online fees show a clear trend: The revenue from download sales exihibit a sharp decrease, whereas ringtones fees dropped significantly. The growth rate of streaming and webcasting fees significantly slowed down in recent years (figure 2).

?

?

In addition to increasing digital and online fees, the broadcasting mechanicals showed also a steep increase of 97.2 percent to AUD?9.1m from 2007 to 2011, with a remarkable jump of more than 50 percent from 2009 to 2010 due to an agreement with the commercial radio industry in Australia.[2] Whereas the collections from educational licencing have remained stable since 2007, the income from business-to-business licencing has significantly decreased by 25.6 percent in real figures over the past five years. Whereas the non retail business remained more or less stable, the synchronisation business[3] substantially declined by 83.7 percent from 2009 to 2010. The revenue from so called ?production music?[4] dropped as well by 22.0 percent ? a loss of AUD?1.2m ? from 2007 to 2011. We can only speculate on the causes for these declines, but it seems to be plausible that the international trend to centralise licencing tasks within specialised agencies and powerful collecting societies negatively affected the licencing business of AMCOS.

?

We, thus, can conclude that the revenue from mechanical fees will likely decrease in the near future, since the revenue from the manufacture of physical products as well as from B2B licencing will further decline. Hence, it is questionable if the increases of broadcasting mechanicals and the digital and online fees can compensate for the losses.

?

The Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Ltd. (PPCA)

The establishment of the PPCA is a result of a fundamental copyright reform in Australia in 1968. The Copyright Act of 1968 granted record labels the exclusive right to reproduce sound recordings, to perform them in and to communicate them to the public and to rent sound recordings on a commercial basis (section 85(1), Copyright Act 1968). Film music as well as music videos were also covered by the Copyright Act 1968 (section 86) and were granted the same protection as sound recordings.

?

The PPCA is a not-for-profit organisation that acts on behalf of its members ? record labels and recording artists. In contrast to APRA/AMCOS, PPCA operates only in Australia and, therefore, labels and recording artists in New Zealand are not included. A part of PPCA?s income is used for the ?Australian Music Pize? and to support several initiatives such as ?Music Matters? and ?The Song Room?. Further a small portion of the collected fees is annually allocated to the Performers? Trust Foundation that gives financial support to several music projects.

?

In a longterm perspective PPCA?s revenue from collected licencing fees has continously increased since 1991. Adjusted for inflation the total revenue ? on average 95 percent licencing fees and 5 percent interest revenue ? has been grown more than twelfefold (figure 3).

?

?

The increase in revenue can be explained by granting more licences, but also by increasing the licencing fees. Whereas the income from licencing has risen by 267 percent from 2000 to 2011, the number of licences has increased ?only? by 66 percent in the same period. Thus, the revenue per licence has grown by 121 percent, which means that on average the fees have been doubled from 2000 to 2011.? In the annual reports of the PPCA we can find some explanations for the rise of the revenue. In 2003, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) agreed to pay higher fees for the music in its TV channels. The disproportionate increase of revenue of 23 percent from 2008 to 2009 was one the hand the result of a decision by the Australian Copyright Tribunal that night clubs have to pay higher fees. On the other hand the PPCA introduced new licence schemes for restaurants and cafes, format shifting[5] and background music on websites. In 2010, the Copyright Tribunal decided that fitness centers also have to pay a higher tariff rate. After a court appeal, however, a new scheme became effect as recently as in 2012.? A successful mediation with commercial telecasters resulted in a new tariff scheme, which involves a substantial increase in licence fees in 2011 in return for a broader grant of rights. Thus, regular tariff reviews supported by decisions of the Copyright Tribunal significantly increased the earnings per licence in the recent years. However, in the early 1990s the income per licence (adjusted for inflation) was very high too. In the following years this ratio decreased to an all-time low of AUD?274 in 2000. The increase of fees and a higher efficiency in collecting them increased the revenue per licence in the following years. Due to new tariff schemes, the revenue per licence has risen to an all-time high of AUD?607 in 2011 (figure 4).

?

?

Since the PPCA does not publish detailed figures on the revenue streams from different licence types we rely on comments in the annual reports. According to these comments the main drivers of the increase were a rise in licencing income from commerical radio stations and a higher public performance licence revenue. The latter licence type does not only include the public performance of recorded music, but also the dissemination of music on different digital formats via the Internet and mobile devices. Thus, we can assume that the growth in the number of licences of about 40 percent from 2004 to 2008 was caused by granting new licences for online and mobile digital music services. However, the number of licences has been grown only modestly by 7.4 percent in the past four years. Thus, we can conclude that the income increase for PPCA was a mix of granting more licences to emerging digital music services on the one hand and doubling the licencing fees since 2000 on the other.

?

The three Australian collecting societies in a longterm comparison

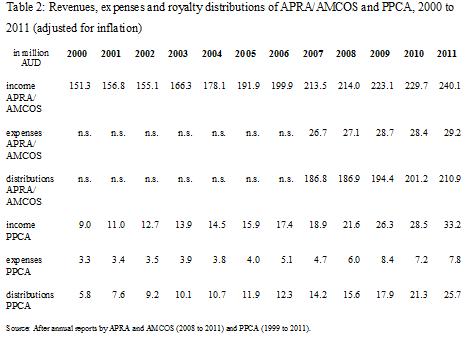

To summarize the analysis of the Australian music collecting societies ? APRA, AMCOS and PPCA ? the revenues, expenses and royalty distributions are compared for the period from 2000 to 2011 (table 2). Since the expenses and distribution figures for APRA/AMCOS are not available for 2000 to 2006, we have only a complete data set for the past five years.

?

?

The longterm comparison highlights that the increase of income of 58.7 percent for APRA/AMCOS (adjusted for inflation) is essentially lower than for PPCA with 267.3 percent. However, APRA/AMCOS could distribute eight times more to their members than PPCA. APRA was also able to distribute higher royalties per head to its members since 2006. Although APRA figures are not available for 2011, the published data highlights an incease of 22.8 percent from AUD?114.3 in 2006 to AUD?140.4 per head (adjusted for inflation) in 2010. Since no comparable data is published by AMCOS and PPCA, we cannot assess the overall distributional effect of the music collecting societies in Australia. However, the APRA figures indicate that most of the Australian writers and composers cannot earn a living from royalty payments by collecting societies. Just a few well-established artists and some of the publishers and labels benefit from the distribution of royalties by Australian music collecting societies.

?

The economic relevance of PPCA has increased over the years. Whereas in 2000 PPCA?s income share in the total revenue of all music collectiong societies was 5.6 percent, the share rose to 12.1 percent in 2011. The prospering business of PPCA and the good performace of APRA contradict the hypothesis of a recession in the music industry in the last decade. The recession has hit only the recorded music market, which is heavily affected by the digital revolution. The emergence of online and mobile music services has partly caused the growth in revenue for PPCA in the past few years, whereas APRA has profited from a growing concert and live music business in Australia by a higher income from public performance fees of live music and concerts, but also from the public performance of recorded music. However, despite a modest income growth, AMCOS will suffer from a loss in revenues from the manufacture of physical products, which will not be compensated by increasing fees from download and streaming services. Nevertheless, the copyright holders will benefit from higher royalty distributions in the next few years. Since no data on the allocation of the royalties to the copyright holder is available, we cannot conclude who will benefit most from the current development.

?

In summary, the analysis of the music licencing business of the Australian collecting societies does not highlight a crisis, but an economic upswing, which is based on new ways of music consumption and music distribution.

?

References:

APRA, 2009, Annual Financial Report, 30 June 2009. Sydney: APRA.

APRA, 2010, Annual Financial Report, 30 June 2010. Sydney: APRA.

APRA, 2011, Annual Financial Report, 30 June 2011. Sydney: APRA.

AMCOS, 2009, Annual Financial Report, 30 June 2009. Sydney: AMCOS.

AMCOS, 2010, Annual Financial Report, 30 June 2010. Sydney: AMCOS.

AMCOS, 2011, Annual Financial Report, 30 June 2011. Sydney: AMCOS.

AMCOS, 2011, AMCOS ? Solutions for Copying Music. AMCOS information broschure for members and licencees. Sydney: AMCOS.

APRA/AMCOS, 2010, An Overview of APRA and AMCOS? 2010 Financial Year Results. Sydney: APRA/AMCOS.

APRA/AMCOS, 2011, APRA/AMCOS Year in Review. An Overview of the 2011 Financial Year Results. Sydney: APRA/AMCOS.

PPCA, 1999, Annual Report 1999. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2000, Annual Report 2000. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2001, Annual Report 2001. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2002, Annual Report 2002. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2003, Annual Report 2003. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2004, Annual Report 2004. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2005, Annual Report 2005. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2006, Annual Report 2006. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2007, Annual Report 2007. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2008, Annual Report 2008. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2009, Annual Report 2009. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2010, Annual Report 2010. Sydney: PPCA.

PPCA, 2011, Annual Report 2011. Sydney: PPCA.

?

?

[1] The conversion in Euros was carried out by the historic exchange rate of June 30, 2011.

[2] In return for an increase in rates over the next two years, the new scheme grants digital broadcast and online rights under a single agreement (APRA/AMCOS 2010: 11).

[3] Synchronisation is putting music with visual images or other effects ? such as in films, television programs, commercials, DVD and online. However, AMCOS does not usually licence synchronisations, except by an agency appointment or as part of a statutory right.

[4] ?Production Music is music which is specifically written and recorded for inclusion in audiovisual, audio and other productions. Production Music cannot be obtained through normal retail outlets and is available from AMCOS Production Music suppliers for convenient and cost-effective synchronisation and dubbing into such productions.? (AMCOS 2011: 11).

[5] Format shifting allows the holder of a public performance licence to make copies of recordings for the purposes of playing them in the licensed venue (see PPCA 2009: 3).

Like this:

Be the first to like this.

barry bonds hazing colton harris moore hurd hurd christopher hitchens ron paul 2012

No comments:

Post a Comment